Interview: Disco Elysium Team

Anyone with a keen eye for truly literary RPGs should be drooling at the trailer for Disco Elysium (formerly titled No Truce With The Furies), a police procedural isometric with sci-fi/fantasy overtones under development by ZA/UM. With input from Art Director Aleksander Rostov and Lead Designer Robert Kurvitz, the team chatted with me on their project. (note: the game’s name changed in early 2018, so I have left NTWTF as the project abbreviation in questions and answers)

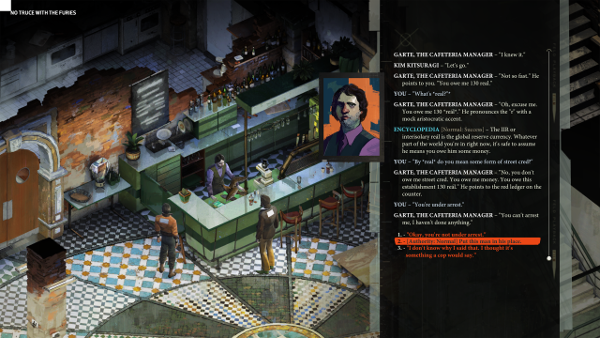

Erik Meyer: For anyone who lived a life saturated in RPGs like Fallout, Planescape: Torment, or Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura, the NTWTF trailer will spark curiosity, and the game clearly seeks to redefine and expand on earlier conventions. With a world created by Robert Kurvitz as ongoing source material and visual assets drawing on an oil painting look from Russian Realist painters, what have been the challenges in uniting these varied elements, and which parts ‘clicked’ the fastest?

Disco Elysium: There’s over a decade of casual, creative and professional collaboration across disciplines embedded in No Truce With The Furies. Writing lead Robert camped out in art director Aleksander’s studio for years while finishing up the novel that set the stage for the world in which the game takes place. We find the RPG a particularly suitable medium for joining the disciplines of art and literature into a seamless, coherent whole.

What’s interesting is how our major themes manifest in different disciplines. The very existence of the world of No Truce With The Furies is threatened by a phenomenon called the pale, which is as natural as the oceans or space. There are edges in this world where reality sort of ceases to exist. And they move around sometimes. Imagine living in this unnerving world – it’s a wellspring for people of character. The very structure of the universe affects psychology, bringing out eccentricities, producing people whose souls have depth. Even simpletons have at some point thought of grand things – you can’t escape those thoughts when the disintegration of the world is not merely an eschatological threat, but a physical reality.

The art reflects this state of affairs. There is a disproportionate amount of color in this world. Nothing is ever just a flat green or red. There’s depth there, the colors get fragmented and mangled into other hues. Flecks of complementary color add spark and life. The white of a plaster wall is made up of so many greens, blues, pinks and yellows. It’s not that you won’t see a white wall. The wall is white, but if you take the time to study it, you’ll find there are other colors in its structure.

Thus, in the end, it all speaks to the same whole. Take any part away, and it’s no longer No Truce With The Furies.

EM: In well-told stories, audiences often come to love protagonists who aren’t terribly likeable (A Clockwork Orange comes to mind); in NTWTF, players assume the role of a disgraced detective in a police procedural drama. To your mind, what is it about difficult situations and dysfunctional narratives that hooks gamers? As you’ve developed locations, NPCs, and subplots, what do you see as essential to maintaining a consistent yet compelling feel?

DE: I think what we like about these characters is seeing other humans being human. We were taught in kindergarten under the teacher’s judgmental gaze to divide people into the simplified categories of “good” and “bad”. We were told the police are the good guys who make sure the bad guys get due punishment. Now we know, of course,that this is not necessarily true. And, forgive me for the triteness of this statement, but the bad guy is just the protagonist of his own story, right?

As humans, we’re a gossipy bunch. There’s something infinitely attractive about seeing into the thoughts and experiences of a character who seems so different from us. It’s also enlightening to see that it’s really all the same stuff that makes us tick. And it’s an opportunity to look into someone’s eyes and see beyond our own reflection.

The really killer part is realizing you can mix that experience with player agency via the magical lightning-blasting-out-of-fingertips medium of video games, which allow you to live that life. And with the incredibly overpowered 4th dimensional super power of saving your game, you can see how far you can push a situation, how insane you can go.

We do not recommend save-scumming, though. Please experience your first run of No Truce With The Furies with full acceptance of the consequences of your actions. It’s better that way. See if you have the guts.

A curious little tidbit: at one point in history, before settling on calling our system Metric, the pen-and-paper version of it was called “Come be a person!”

EM: Literary elements take center stage in NTWTF, including combat via dialogue, a thought cabinet to guide players through old mysteries and new ideas, and a keen connection to a constructed history. As you’ve added elements that bring richness to the game experience, what do you hold as your criteria? What benchmarks do different mechanics need to meet, and what kinds of hard decisions has this involved?

DE: The things we have done, the mechanics we have explored, revolve around bringing fresh gameplay elements into the age-old mechanic of the dialogue. For decades the medium of games has been in a constant state of hurricane stormwinds of mechanical creativity. But, despite this fevered evolution of game design, the Dialogue as a branch of game mechanics has largely been ignored, having been thought of as “good enough” from the get-go. Imagine if FPS games today still had Wolfenstein 3d gunplay: that’s the mechanically stale state that dialogue is in. So much so that it occasionally gets attacked by gameplay-exalting, manifesto-writing designers who want to throw it out as inherently alien to video games, instead of realizing that it’s simply an underdeveloped area of game design.

We’ve taken the systems of our forefathers and tried to virtually run 20 years of video games design process in our heads, so as to arrive at a point where we feel we would be if the development of the dialogue mechanic had not been interrupted.

Should I get into specifics? Some of the mechanics we’ve come up with are the Thought Cabinet, and the red, white and black checks.

Mechanically, the Thought Cabinet offers modulation on your character build. While playing No Truce With The Furies, you talk to people, and find yourself saying some stuff or hearing about something that gives you cause to ponder. This is the Thought Cabinet: you can “equip” thoughts to ruminate over while you play. When a thought is active, it changes your stats, and can give you extra dialogue options or specific bonuses. For instance, the Inexplicable Feminist Agenda gives you bonuses against male characters.

You have a certain amount of ideas you can process, and you can switch your thoughts out, but once you’ve completed a thought or arrived at a conclusion, it results in a permanent change in your character. The fun part here is that these changes can be counterintuitive. After a serious session of philosophizing, you might become enlightened and get bonuses all over the place, or come to the conclusion that the idea was terrible and irrelevant altogether, or it might wreck you with crippling depression. It’s all fuel for roleplaying.

The black checks are passive checks that happen in the background and tie into our skill system. In our system, your skills can talk to you. Have a high enough Drama skill, and your conversations get interspersed with Drama commenting on how someone is obviously lying, thus giving you a deeper understanding of the situation. A high Half Light, a sort of strongman adrenal gland skill, can give you violent dialogue options and incite you to act on them. The black checks represent your inner impulses and psyche, and, depending on how you want to roleplay your character, you can listen to them or ignore them. They’re not infallible either and can get you into trouble if you’re not careful.

The red and white checks are dialogue options for which you roll the dice to see if you fail or succeed. Most dialogues are written to have one such check in it. White checks are simple enough. Say you’re trying to deduce something using your Logic skill. Your stats and skills get added up and rolled against the difficulty of the white check, and you either deduce something or you don’t. If you fail, you can try again later. Red checks are the juicy ones – succeed or fail, you have to play through the consequences of your actions. A red check failure is that garish pick up line you botched and can’t back out of. You’re locked into it now, the horrible situation plays out line by line, you’re digging yourself in ever deeper, thinking, “Oh sweet Jesus, why did you have to say that”? Sweet honey-dripping awkward until the merciful end.

And here is where the interconnected nature of dialogues in No Truce With The Furies shines. Depending on things you’ve said earlier, you can get bonuses or penalties on these rolls. Broke down crying in front of a girl? She might feel sympathy for you. Add to that whatever thoughts might be lingering in your head and the social effect of the clothes you’re wearing (hint: bellbottom pants really do not make you look authoritative!). All of this is weighed when you’re rolling for that red check.

This rhizomatic, interdependent web of modulation is what brings the dialogues to life. We want to write dialogue that IS the game – as fun to navigate as 3d worlds, as fun to play as tactical combat and as enjoyable to read as any good book. Them’s the criteria for our systems design.

EM: You’ve spoken in other interviews to the fact that details and personal connections bring worlds to life. NTWTF celebrates the unique, multi-millenia timelines of numerous civilizations; here on present-day Earth, many people remember the Roman Empire by way of togas and cool architecture, much as they remember the ’80s via Deloreans, Moon Boots, and He-Man. For the game universe, how large is this role of inherited memory, and what kinds of influence do you see its minutiae exercising?

DE: These elements permeate society in No Truce With The The Furies. People wear belt buckles with ornate lung designs as a reference to Innocence Dolores Dei, a benevolent maternal zeitgeist-defining semi-religious figure who lived some centuries ago.

To take a step back, all of today is accumulated history, and, whatever Fukuyama might have you believe, history is never done. When we think about the world we’re creating, we don’t think in terms of snapshots of a perfectly composed world. Fictional worlds often suffer from stasis, where the demiurge designer fixes the perfect moment down with superglue. To counteract this, it helps to think on a grander scale, to see things in terms of historical processes building up and eroding away. People may live in houses built a hundred years ago, but life today is different from what it was like then. The old gets modified for contemporary use, though the origins remain plain to see. What we’re doing is applying dialectical materialism to world design.

Movements and tendencies that will shape the future are also already at play in their nascent forms, and in No Truce With The Furies, just as in our world, if you pay enough attention, you can almost glimpse the future.

A nifty midway point that our world occupies is that we have the mass production of swords. They’re forged, pulled, hammered, bent and grinded by heavy industrial machinery. The handles are cast in bakelite resin. Final assembly is by the underpaid proletariat huddling around lengths of conveyor belts. And these swords are surrounded by familiar debates: some people feel they’re not of the same mettle as the old smith-forged swords with their arabesques on swooping hilts, the narwhal and giraffe designs, while others see the wonders of the modern world, the cost savings of industrial automation, bold aesthetic simplification and mechanical perfection – the democratization of the sword.

In our world, there are people pining for the old days of monarchs and cavalry maneuvers, and there are people who look forward to robots with magnetic limb sockets. There are people who know that you can split the atom.

EM: Technology in NTWTF has progressed on a course roughly parallel to our own, with civilization leading to something akin to Modernism. Describe the advantages of making cars, but cars that don’t quite look like our cars, or tiled floors that appear familiar yet askew. How do you leverage this connection to gizmos and know-how?

DE: What it really does is lend credibility to the world. The desk telephone is the single most realistic invention in the history of mankind. As powerful as the wheel, as boring as sliced bread. Normality is boring and there is secret power in that. Normality gives us the ability to see ourselves in this world, we can imagine a mundane wasted day among telephones, corner kiosks and bus stops. And this is the sweet spot for juxtaposition, but you don’t necessarily have to go full fantasy to achieve it. For instance, have you ever seen a horse in a city? That’s a moment in which anachronism is embodied. The horse immediately speaks of medieval knights and wild west cowboys, and even though today it is relegated to breeding ranches for annoyingly wealthy people, these embedded historic images surface, and seeing this majestic animal trotting down the street between gridlocked cars is amazingly jarring. And that’s the kind of feeling we want to take and multiply tenfold.

EM: Each developer/studio has its own way of doing things, and the ZA/UM artist community includes people of varied talents, bringing unique perspectives to your work. In terms of streamlining these talents into game design and progress, what does your process look like?

DE: There can be a lot of back and forth, and sometimes passions do flare up. You’d expect as much from any creative collective, though. A lot of our people have creative backgrounds, from writing, painting or running D&D games. This gives some common ground to understand that things aren’t great until you suffer through the bad.

There’s a feeling of vulnerability in effect there as well. It takes almost nihilistic bravado to have the guts to show people your works in progress. It’s necessary for the collaborative process, but it can be difficult to press on with merely the hope that your peers see something you’re working on beyond its current sorry state, that they can gauge the possibilities therein. But that’s the nature of the beast: to make something grand, you go through an iterative grind of culling bad solutions until you’re left with the okay. And sometimes you need to have the courage to throw out the good to get to the great.

In this spirit, we have redone entire areas and rewritten entire characters in No Truce With The Furies to fit better with the whole. There’s a tour of shame hidden away on our hard drives, early concepts of places and characters you wouldn’t recognize. Mechanics and design ideas left mangled on the cutting room floor. If there’s one idea that can be hard to impart on more pragmatic people, it’s that it’s shit until it’s great.

We sincerely believe that it’s better for the artist to leave the art undone if it’s not good. Look at your Steam library. Nobody needs another game released. We don’t want to work on just another game. What we need is a masterpiece, and so we do what we must.

EM: I’m curious about your take on stats versus storytelling and how you see the two as connecting. You’ve mentioned that the game has 24 skills and 4 attributes, noting impacts on the playing experience. If a player starts down a specific path, does it become difficult to ‘change lanes’, and to what extent are players rewarded for consistently maintaining a particular ethic?

DE: In terms of classic RPG dichotomies, there are no lanes to follow in No Truce, no paragon or renegade archetypes to choose between. Instead, the skills and their influence on the plot form a complex interwoven structure, revealing different aspects of the plot and the world as you play. Some of these might even be contradictory, resulting in straight up cognitive dissonance in your character. You can build a really schizophrenic type, whose skills start arguing against each other and vying for the player’s attention.

However, there are more concrete archetypes you can settle into if you wish. We have political leanings in the game – you can be a hard core nationalist, a communist, a “radically centrist” neoliberal we call moralist. O ye boring person of meager soul, raise high the moralist flag of signal blue!

While playing the game, you get these little snippets of choice where you can demonstrate your leanings, and, as the game goes on, you get associated Thought Cabinet projects to ruminate over your ideology and get the relevant skill bonuses. And if you really fly the flag, you can do a kind of a vision quest for your ideology to cement your beliefs. This might involve having a fevered conversation with the broken down statue of one of the old Philippian monarchs, sword in hand. Or it might not! Design in process.

(Insert more money for awesome political vision quests)

EM: You’re developing relationships via Humble Bundle, social media, and the public at large. What responses have surprised you along the way? What kinds of connections do you see forming within the developer community, and how do you see your movement growing?

DE: What we’re really trying to get to is a community of video game designers who view their work as carrying responsibilities beyond those of a toymaker. In video game culture, we have this destructive adoration of fun which rules as an idolatrous tyrant over all other considerations. You can uncover downright scary fundamentalist rage online if you have the gall to challenge this tenet.

For me, the fact that we call these creations “video games” is essentially an etymological curiosity. They have long since stopped being games.

This is a controversial enough statement that it should probably be supported by additional statements such as: shit video games can also be fun, but that doesn’t make them good. Good video games can be not fun, and that doesn’t make them bad. Fun is an aspect among many, and it’s harmful to elevate it above others. A thing doesn’t have to be fun to keep you engaged either – it has to be engaging. We should be wreaking havoc on internet forums demanding for games to be engaging!

Oh, but I digress. We’re trying to reach out to developers who take responsibility for their creations, who see their work as more than bleak entertainment. Creating games is an opportunity to challenge, to enrich, to stir emotions. And the hope is, if you get these people – these designers, companies and authors – together, you can start doing something. That’s how you get a voice, say something and have people hear you, get out of the video game ghetto and impact humanity and culture at large.

And you know what? If to add what the community has taught us or what relationships we have made, then we have really been thinking about localization and porting. It is not just an industry thing to consider in need to reach wider, no, a lot of it is your fans and supporters asking for it. Linux lovers is a whole universe and man they are loudspoken! These kids literally say: “Look, I do not live with my mum, I work and will throw money at you if you fill our wishes. And there is detective story lovers who want to read in their own language and they have voiced their needs to us and we really want to answer to that by delivering to those who asked.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NE2MMpKiJCk

Also, here are a few rare shots of the NTWTF leads from years back:

(Rostov-in-his-studio-2012-2013)

(Robert crashing Rostov’s studio 2012-2013)