Interview: Children of Morta’s Javid Najibzadeh

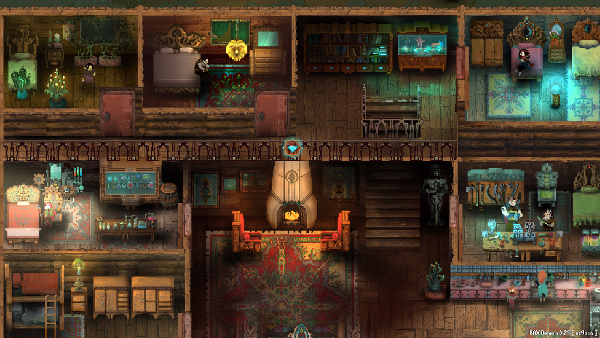

As a pixel-art family epic roguelike adventure game, Children of Morta brings the creative satisfaction of a ’90s console title, adding 21st century sensibilities. With multiple playable characters and lush environs in crisis, the game has buzz, and I chatted with Javid Najibzadeh of Dead Mage regarding his take on things.

Erik Meyer: Children of Morta follows the Bergson family as they seek to undo the damage done to the mountain by dark forces. Out of curiosity, how did the ancestral home aspect of the game develop? Unlike a game like Hyper Light Drifter, we have multiple player options; what spurred this connection to stewardship and kinship?

Javid Najibzadeh: We stepped right into this as big fans of roguelike games and action RPGs. From the very beginning, we all had our minds set on giving birth to a narrative hack’n slash with plenty of roguelike elements. We wanted every player with any play style preferences to be able to play the game and just jump right into the action with the class he is most comfortable with. By creating multiple playable character classes, we wanted to fulfill that (8 playable classes? What were we thinking back then? Grrrrr ). As we continued our journey on our new project, we began to realize it was somehow not cool that these characters were not related in any way. As the characters began to materialize, we really wanted them to somehow share a bond. We also wanted the players to have some sort of feeling of still being in the game when they die in a dungeon and are thrown out of it, a hub perhaps! It all began with the idea of an inn where beaten-down knights and heroes gather to spend the night, have a drink, and prepare for their next adventure. We were brainstorming and exploring other options when we found our answer! A family with playable characters as its members, and of course their home as the hub! Suddenly all the bonds began to form, and the children of Morta were born.

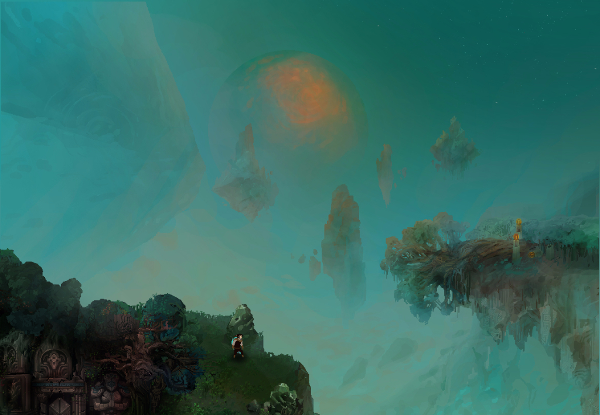

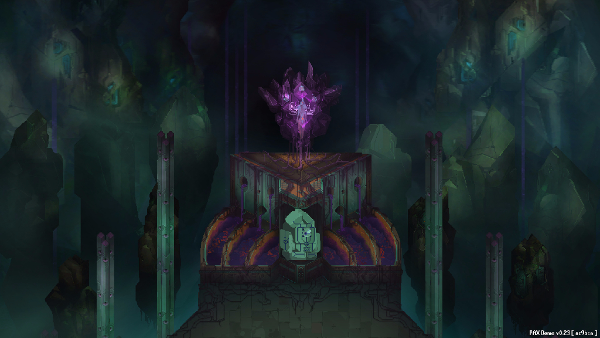

EM: The game’s pixel art includes beautiful landscapes, unique battle graphics (such as Fire and Wind), and quiet moments in lush forests. As you’ve added details and locations, what do you hold as visual goals for assets, and what do you use as a guide (color palette, character models, overall consistency)?

JN: We have aimed a unique spot between old school pixel art games and modern 2D games. It has been quite challenging, but so far the results haven’t been bad. Another main source of inspiration is eastern art and mystic aesthetics. We only have two artists, Soheil and Arvin, and they do the magic of making sure everything is consistent.

EM: Occasionally, gameplay stops, the camera zooms in, and a narrator supplies context for the events taking place. As characters embark on an epic saga, what kind of balance do you try to strike between cutscenes, dialogue, and adventuring? Where does it get tricky?

JN: We want to use as few cutscenes as necessary to help and push the main storyline of the game forward. The narrative in general is divided between fixed events that comprise the main story arc of the game and procedural events which help the gamer get to know the family members much better and experience their stories. This balance has been quite tricky, not many games have targeted this feature before in this genre.

EM: Between normal attacks, special attacks, character abilities, evading, and divine relic use, players have numerous options at any given moment. What did these mechanics look like early on the game’s development? What options have changed as you’ve gone along?

JN: At the early stages of development, each playable character had 3 abilities: Primary Attack, Secondary Attack, and a special ability. It was all much simpler than how they are played now. Even dodging was considered a unique ability of a certain character, and not all characters could perform it. Now, all players have the dodge ability from the very beginning, in addition to many more abilities of their own or what they can find in the dungeon. To spice things up, we added ability runes. Players can find them in the dungeon runs now. Each main ability has various runes that alter that ability in a specific way. This intends to bring some play style and also to provide some variation to the runs. Last but not least, we figured out that divine relics were something that had the most effect on distinguishing one run from another. So we decided to double the divine relics and even provide the player with an extra active divine relic slot. We of course didn’t intend to bombard players with all these potential complexities from the beginning, so we decided to unlock them as players progressed. A progress which is permanent for each playable character and doesn’t reset when a run is finished.

EM: As a studio, how do you work most efficiently, and to what degree do assets get planned before you start to flesh them out? Do you do mock-ups, or are there individuals who have license to simply make an asset, and then supplemental work happens from there?

JN: Our core development team included two senior programmers, two artists, three gameplay programmers/designers, a sound designer/composer, and a writer/designer for most of the development process. There were others who occasionally joined us and helped, too. Our senior programmers came up with a range of useful tools and systems, in pre-production and later on, that made Unity an even better engine to work with and provided our gameplay programmers with a lot of features to create content more productively. From then on, gameplay programmers would create content and drop it in for testing. (Without even knowing the consequences! That would submit the artists to the cruelest slavery of their lifetimes.)

I think the scale and quality of the art and animations and the variety of content already in the game and in progress, considering that there are only two artists on the team, speaks for itself. There have always been tons of art tasks weighing on their shoulders. Despite their utmost devotion and long working hours, tasks were usually pending. And we couldn’t stop waiting, so we usually continued creating new features and content with placeholders or mock-ups before the artists could take turns tending to them. We had to wait and stick to those mock-ups and have our fingers crossed that this would one day shine in our game. And to our surprise – but not anymore – our artists’ magic always did the trick.

EM: I note that most games draw from a rich trove of lore (history, magic, game universe, etc), much of which doesn’t make it into the final version. As you’ve progressed, which elements have become vital, and what have you had to leave out for now?

JN: Oh, we’ve had a lot of ups and downs regarding the game lore and story, and one thing which has always helped us is to have in-house narrative designers who can tweak and change things based on the expected developments and gameplay constraints.

EM: The crafting and procedurally-generated elements of the game deserve mention. As developers, you want to encourage customization and multiple playthroughs, but you also need to provide a balanced experience, so what kinds of challenges come with adding these features?

JN: Creating a good pace in the game requires one to keep the game in the right flow away from frustration or boredom. This is much easier said than done, especially in a roguelike game where you are using tons of random or procedural elements. There is always the risk of a player dying too soon in consecutive runs and abandoning the game. On paper, randomness does balance itself out in the long run, but some players can’t wait that long. So from time to time, and not always, you need to be generous. Give the player a taste of how powerful they can become. What makes one want to jump right back into the dungeon of death just after being slain over and over again? The new things can happen. The element of surprise can always wait there for you, mainly because of randomly generated worlds. In Morta, we added layers of permanent progress to that, as well, to maximize the chances of our players staying longer. There are also procedurally-generated events and quests that happen in the dungeon which result in cut scenes or events to trigger at home and generate even more quests in upcoming runs. By doing this, we are hoping that our players keep heading back in there with new goals besides their main one (and to decrease frustration as much as we can).

EM: While the game stands as a roguelike hack’n slash, it also quotes the point-and-click adventures of yesteryear. As tools for game creation continue to develop, where do you see indie games heading?

JN: Games continue to evolve. When we were a bunch of kids, I remember genres were much fewer. There were adventure games, roleplaying games, action games, platformers… As technologies grow and platforms expand, new opportunities arrive, and new things are born. Who thought of text-based adventures before computers where born? (Or maybe they did but that is not the point). Let’s mix a bit of this and then add a bit of that and action adventures are born. You just called Morta a roguelike hack’n slash; who knows, maybe the next one would be a point and click roguelike hack’n slash RPG with 4x elements!

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer: