Interview: The New World’s Vince D. Weller

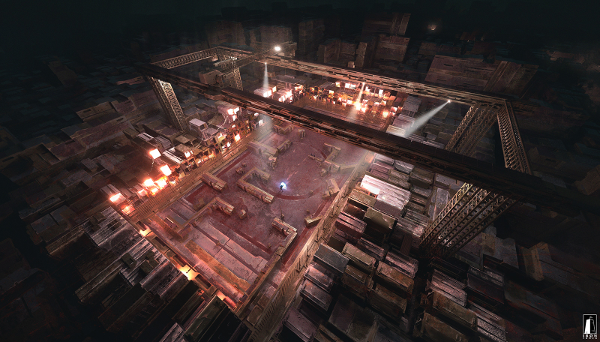

Inspired by Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky, Iron Tower Studio’s Colony Ship (formerly titled The New World) stands as a turn-based generation ship RPG with a style that should turn the heads of sci-fi purists and Fallout fans alike. With striking concept art and the team’s highly detailed updates in mind, I chatted with lead designer Vince D. Weller on the project’s finer points.

Erik Meyer: The New World draws inspiration from Heinlein’s writing and the Fallout series, so from a setting and atmosphere standpoint, what must-have elements do you take from these predecessors, and what do you see yourselves adding to these iconic works?

Vince D. Weller: From Heinlein we borrowed the concept: a colony ship flying through space for hundreds of years, many generations destined to live and die on the ship, all in the name of an idea nobody remembers or cares about, with eventual mutiny and loss of purpose.

As for Fallout, it was the first game (for me, at least) that shifted the focus from killing and looting to dealing with people and exploring different ways of adapting to this new post-apocalyptic reality.

From this perspective, there isn’t much we can add there as it’s a direction rather than a formula, so we’ll continue exploring this direction further and focusing on factions, choices, and dialogues.

EM: The fact that the game world is a generation ship gives you a certain freedom as storytellers to repurpose the habitat and the cultures/religions/daily lives of the populace to your own ends. You can create factions that arise from the needs of spacefaring people, so what unique challenges come with fleshing out NPCs, locations, customs, and the quirks therein?

VDW: We prefer to stick with realism whenever possible. As Joe Abercrombie of The First Law fame said, “Now some folks might say, “hey, it’s fantasy, it doesn’t have to be real,” but I’d say the exact opposite. It’s happening in a made up place, so it has to be more real than ever.”

Thus, our main challenge is how to make the factions and characters (motivations, beliefs, agendas, goals, etc) realistic and believable in the context of the ‘made up’ setting. To do that, we turn to history: the French and Russian revolutions are a handy guide to class warfare, reigns of terror, and post-revolution factions, the early days of Deadwood are a good blueprint for our container town, plus the fascinating story of SMS Königsberg, New England’s Puritans, etc. It’s quite a mix but the same could be said about the AoD world.

EM: I notice characters have a fair amount of stats that (like Fallout, Arcanum, or Shadowrun Returns) respond to different play styles, so what is the guiding philosophy behind the numeration of attributes, and as you tweak/incentivize with equipment, how do you work to keep things balanced?

VDW: Since both your character and the allies/enemies are using the same character system, we’re relying on the system itself rather than on inflated values. Thus, stats and skills matter a lot for the player to feel the difference between a thug and an experienced fighter or between an experienced fighter and an exceptional fighter (a ‘hero’ who happened to be fighting for the other side and is dead-set on murdering you for the greater good).

Thus, a thug would have 6-7 in physical stats and 3-4 in weapon skills, a good fighter would have 7-8 in stats and 5-7 in weapon skills, and an exceptional fighter would have 9-10 in stats and 8-10 in skills. Nothing you character can’t achieve if he or she lives long enough.

The combat system itself is based on and balanced by the trade-offs. The 3 main variables are to-hit chance, damage, and action points. You want to do more damage? Then try more powerful attacks that are slower and thus easier to dodge or block. So your damage goes up (if you land a hit), while your attack speed and to-hit chance go down. You want to hit a lot? Do faster attacks that but you won’t do as much damage. Stats and gear modify this equation, so what’s true for your character won’t be true for someone else’s character.

Overall, we have 6 traditional stats, a bunch of derived stats, and 21 skills. Our goal is to give the player 4 distinctive paths to follow:

– Combat specialist

– Infiltrator (stealth, lockpicking, critical strike, etc)

– Diplomat aka scheming bastard

– Jack of all trades, master of none

EM: Iron Tower has a fair amount of experience under its belt (I’m thinking The Age of Decadence), so how do your past projects and successes inform your current processes and pipeline?

VDW: Considering that it took us 11 years to make AoD, that’s a lot of experience. Essentially, this experience is a mix of knowing how to do something (vs doing it for the first and hoping you get it right, which doesn’t happen often) and knowing what works and what doesn’t, which is probably the most valuable knowledge there is.

Other than that, we’re still a small team (we added another programmer and a 3D artist), so our pipeline didn’t change that much.

EM: You explain the inspiration for The New World title on your website, noting the parallels between the era of explorers/colonization and humanity’s desire to reach for the stars. In following, you note that the First Generation of ship inhabitants maintained a drive and an optimism that fell flat in the generations that followed, so to extend that thought, what is it about exploration that draws some people to leave homelands in search of fortune on foreign shores? And as generations become accustomed to the new space, how do we avoid stagnation?

VDW: If John Glubb (the author of The Fate of Empires and Search for Survival) is to be believed, we can stop stagnation no more than we can stop winter from coming. It’s a seasonal thing.

So it’s not that the new generations become accustomed to their new world, it’s that each generation moves further away from the beliefs of their fathers and forefathers, eventually coming full circle. The ancient Greeks noticed it first and our nature hasn’t changed much since then. We worship different gods and have different values, but our hardcoded nature remains the same. Note to aspiring developers: don’t hardcode things, nothing good comes from it.

As for what draws people to leave their homes, I’d say it’s the promises of fresh starts and great opportunities (because the grass is always greener on the other side and the faraway lands are overflowing with milk and honey, which is a well-documented phenomenon).

EM: Another big theme of the game seems to be grit, a keen disillusionment on the part of NPCs and the people in charge, so in a world filled with chaos and desperate people, what does the profile of success look like? Is it as simple as being really good or really evil, or what other personality/archetypes win the day?

VDW: No matter how bleak things were in different periods in our history, there were always faction leaders and various opportunists who did pretty well for themselves. In fact, many believe that periods of chaos offer the best opportunities to rise above your station and redistribute some wealth in the process.

The Thirty Years’ War was one of the bleakest points in the history of Europe, yet for Albrecht von Wallenstein, an impoverished noble born to a Protestant family, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to become a supreme commander of the armies of the Holy Roman Empire and a major player in said war.

Similarly, most characters who’re doing well in The New World owe their success not to being really good or really evil but to being able to adapt to the ever-changing circumstances better than most, recognizing opportunities and taking advantage of them before anyone else does. Survival of the fittest.

Here is one ‘success story’:

Thomas Stanton had always been good with guns so it made sense that’s where he would make his living. Robbing traders and prospectors would have been the obvious choice. The payoff was quick but picking targets was risky work, and the chance of a fatal error always high. Instead, he organized a small crew to offer protection services. They called themselves Thy Brothers’ Keepers and quickly established a name for reliable service in the Wasteland.

It was around this time that traffic through the Factory sharply increased, and when Tommy caught wind of the escalating violence that came with it, he smelled opportunity. He relocated his entire operation to the Factory, a decision which at first looked like a serious mistake. The Keepers lost more men on their first day in the dead city than they would have on a paying job. In return they had advanced all of four blocks. That’s when the idea of the Toll Road was born.

Leaving the rubble-choked ground level to the gangs, Tommy and his Keepers secured the remains of the rail overpass and the upper floors of a few key buildings. High above the strife and mayhem of the Factory floor, they began work on establishing a safe route through the area. The first month was rough; their waypoints were attacked almost daily. But the ragtag gangs didn’t have the organization or mentality to maintain a real siege. The Keepers fortified their positions while their attackers received an education in the many disadvantages of attacking from low ground.

The rough part is all behind them now, and Tommy’s business is flourishing under the best conditions: he offers what nobody else can, and is free to name the price for his services. Since Tommy decided on quite a high price, he’s also keen to discourage competition. The Keepers have a standing order to fire on anyone armed or suspicious looking who isn’t under their protection, making it impossible for anyone else to get a foothold in the Factory.

As you can see, Tommy is neither good nor evil, although he’s done both on some occasions. He resisted the temptation to go after the easy money and provided a much-needed protection service. Then he smelled an opportunity and established a toll road through a dangerous area. Of course, now that it’s established, he’ll do whatever it takes to keep the rivals from establishing a foothold in that area, but that’s a different story.

EM: Even now, in our modern world, specialization means most people don’t know how to do everything. One guy might be a good carpenter or a good plumber but know nothing about fixing a cell phone or a laptop. As the technology of the First Generation has fallen to subsequent generations, what kinds of taboos and or unique, marketable talents can we expect to find? Has technology come to be viewed as something almost magical, or has it simply become mundane?

VDW: Imagine a modern cruise ship’s passengers being marooned on an island. They won’t forget how to use a computer or a cellphone, but they won’t be able to build one from scratch without proper resources or to maintain their electronics indefinitely, so they will have to ‘switch’ to lower tech out of necessity.

Same here. The Ship’s inhabitants can use high-tech weapons and gadgets, but they can’t build new weapons and devices without having access to proper machines and supplies. Instead, they make low-tech weapons and devices because they are relatively easy to produce. You can’t make new plasma cells, but you can make bullets using synthetic propellant. You can’t make plasma weapons, but you can make good ol’ fashioned firearms (ranging from crude to high quality guns made from machined parts).

So the new marketable talents are gunsmithing, metal forging, scavenging the Ship for anything valuable, from Earth-made weapons and gadgets to implants in mummified corpses, and reactor maintenance.

EM: I’d love to hear about your process at Iron Tower, in terms of content creation and decision making, so when you come up with ideas for a new feature, what does it look like from genesis to completion? Do multiple people put their heads together and confirm what they need to complete the tasks, or is it more of a top-down managed environment?

VDW: We’ve worked together for over 10 years, so we know each other well and we trust each others’ judgement. So let’s say I (as the lead designer) suggest to do something a certain way (for example, how to handle the weapon slots) and Nick (our programmer) says it’s not a good idea. I trust his judgement on it without getting into lengthy conversations about it.

Overall, when a new feature is proposed, if someone has a concern of any kind (implementation or design), he raises it and we discuss it until we all agree on how to proceed. The concern acts a red flag here, so it’s more about evaluating this feature from different angles, rather than making sure that everyone has a say.

Basically, we have a “culture” (for the lack of a better word) of not taking criticism personally and considering each and every suggestion. As a result, nobody thinks twice about sharing their concerns, expecting them to be addressed. Simple as that.