Interview: Totem Teller’s Ben Kerslake

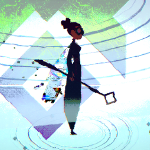

A game about discovery and yarns by Grinning Pickle, Totem Teller drops players into a beautiful world of broken narratives, astonishing its audience with a landscape that evokes a psychedelic fairy tale aesthetic, bringing bedtime stories into the 21st century. Enraptured by visuals, I chatted with dev Ben Kerslake on the impetus behind and methods driving his work.

Erik Meyer: Before looking at anything else, I was struck by Totem Teller’s art, which has a very hand made, paper-texture-with-blotted-paint feel. I’ve alternately found it mesmerizing and familiar, like a CRT monitor dying in the most beautiful way. So how would you describe your use of glitch FX and the visual picture storybook strategy therein; how interconnected are the game’s main themes with the world we see?

Ben Kerslake: I’ve always been obsessed with how various forms of processing affects traditional art. I think it started when I was a kid. Some games used scanned, hand-painted artwork as backdrops. I found the visual artifacts produced through the reduction of detail and color brought a new kind of beauty to these images, something not present in the original. In art school, I remember being similarly affected by seeing my own images go through the physical print-making process. It transformed them into something no longer mine – I could appreciate them purely as an observer.

All the glitch effects we use stem from the desire to weave the theme of transformative processing into Totem Teller. It also had the benefit of supporting the idea of stories transforming as they’re retold – they’d change, and no longer belong exclusively to the previous storyteller. A process of gaining through loss.

EM: From a story standpoint, you’re asking players to restore a world and make a new mythology while losing themselves in something broken and beautiful, so when it comes to your use of writerly tools, how do you approach pacing, exposition, narrative arc, and similar elements within the context of an electronic user experience that asks players to sift through scattered plot points, piecing things together? As compared with the written word, how do you translate from the page to the screen?

BK: The short (perhaps trite) answer is that I do not translate from page to screen. Written content accents the experience, but it does not define it.

There is no set story arc that the player must experience. Scattered, broken folklore/mythology inspires the world player explores in Totem Teller. It is exploration and revelation of the connection between world and story that motivates. I’m doing my best not to prescribe what the player ought to feel or conclude.

Enforced pacing and traditional narrative flow can make for a great story alongside a game – but believe they’re a detriment to the methods of storytelling uniquely possible in games. Totem Teller is built around moments (the titular totems) where the player chooses to change things in the world – some story related, some aesthetic. I wanted those choices to be based on gut-feel rather than the player acting out a role I’d defined.

I should mention that I didn’t start things this way — originally, I had a very typical story arc with the player character as the protagonist. As development progressed, this approach felt less and less relevant to what we were building. I pared it down again and again, until it was gone. Totem Teller is very much about unresolved, liminal places and ideas. A tightly written storyline just felt wrong.

EM: You’re very good at creating a peaceful, natural atmosphere in a setting with bold colors, often accomplished by swaying grass and trees, waterfalls, ripples, and other effects that suggest slight movement; I’m curious about this careful use of atmosphere and how it fits in with your design philosophy. What is it about these images that evokes this sense of tranquility, and how does it help your project in doing so?

BK: Attention to these details, I hope, reflects a general reverence for the natural world. The ultimate inspiration for storytelling and creation in general. The earliest prototypes for Totem Teller, before the art and story themes had solidified, were built around an open-ended pilgrimage through nature.

Eventually, as I gathered more of the folklore referenced in Totem Teller, the different natural settings have become connected to specific cultural/story roots.

EM: You’ve reworked the protagonist a bit over the last year or so, noting a need to nail the art style before revealing and solidifying the Teller and other characters. You’ve also noted the gameplay mechanics are focused on choosing how to repair that world, but when it comes to the setting’s inhabitants, what strikes you as important, must-have qualities (visual or otherwise), and what aspects of traditional game NPCs need not apply to your project?

BK: The main challenge I’ve had in designing both the player and other characters is having them serve archetypal (or symbolic) roles, rather than ‘starring’ ones. I discarded many early designs because they felt too special, individual – good traits if you’re trying to build your game IP around charismatic characters, but I wanted this experience to be primarily driven by the player relationship with the world and the creative process. So the cast of characters must be subdued in design, familiar – without being boring.

Much like the writing and world art, character design has been a process of reduction, cutting as much design fat as possible. As far as what we’ve shared online, leading with characters always felt wrong. Though our characters are important, they exist to serve the world and its stories.

EM: The atmospheric music for the game feels both dreamy and otherworldly, complementing the visuals well (I feel like the words ‘haunted in a root cellar lit by a disco ball covered in stained glass’ describe my sonic response), but from a dev point of view, what do you see as the overall effect of the audio, and what goals do you have for the interplay between what we see and what we hear?

BK: We’ve not released much of the music publicly (just one very early exploration theme) – so I’m not sure what you’ve heard 🙂 Either way, your description is apt. Music is so incredibly important to any game, but especially so for one like ours. We’ll need a lot of it, and we’re setting the quality bar high.

Musically, we establish a settled, relaxing ambiance that carries the theme of each Telling (a distinct biome + story). Our world isn’t just about natural spaces, but liminal ones. There’s also a heavy suggestion of the synthetic or virtual. Music must reflect a balance of those motifs. Beautiful and broken. Synthesis of the natural. We also apply procedural distortion to music in complement to the visual glitches.

EM: You note on your site that Totem Teller started as an idea for onegameamonth.com and became a full-time project two years later, meaning you had an extended period for notions and concepts to percolate. As a part of that process, what were the turning points, the decisions and moments that changed the trajectory of your work, leading you to where you are today?

BK: Primarily those I’ve mentioned, especially in regard to implementation of story – moving away from a typical narrative arc and character driven drama beats. Embracing the idea that Totem Teller a fully explorable illustrated compilation of folk story snippets that must be resolved and committed to a final retelling.

The art style iterated through two abandoned approaches before we found the right fit. I’ve poured a lot of time into finding what we’ve settled on, and refining it since. In the end, it was about being creatively honest – really committing to the style and themes that inspired me. The project as a whole represents that honesty, so the art should follow.

What hasn’t changed is our emphasis on open exploration and a player paced experience. Making discoveries with minimal to no guidance, and making choices without a right or wrong answer. Giving the player a sense of authorship.

EM: In reading your developer log on indiedb about the beach area creation, I note your keen attention to the technical process (a sketch with major location features and relative asset scale, use of the lasso tool and a mono palette, then the creation of specific files grouped by type, followed by a mock-up and syncing of images, importing everything into Unity, animation with a focus on timing, deco, FX, and polish supplemented by a script to aid in the process before moving to inland areas), a process which strikes me as the tip of the iceberg, when it comes to your work. As a dev, would you say the inspiration for what you do comes from an internal sense of vision, or do you feel yourself responding organically to new tools and concepts that come from the process of working on the project? Similarly, what kinds of technical hurdles do you encounter on a daily basis?

BK: We are constantly working at improving tools that help implement art and design. Thanks to Jerry (technical lead), I’ve moved more and more of my workflow into Unity – this makes revision, which I tend to do a LOT of, faster and relatively pain free. As a two person team, with me implementing all the art, our tools can be built specifically to my needs. It’s a huge advantage, and I know it’s saved us countless hours of work. My general process is still the same, but I spend more time working with final assets and making practical design decisions.

Inspiration comes from all kinds of places, still – but the deeper I get into a project, the more I’ll be influenced by the realities of implementation. I know what to spend time on, and what to skip. I have always worked on the conceptual and execution side in tandem, so I think my vision is always kept in check by the project limits. Limitation is a good thing, though – you can’t achieve style without it.

EM: In conversations about games as art, titles like Kentucky Route Zero, Bendy and the Ink Machine, and What Remains of Edith Finch come to mind, so as videogames become more nuanced and genres continue to emerge, what do you see setting the bar for literary depth, and what aspects of craft separate electronic media from the works of Ray Bradbury or Kurt Vonnegut or Raymond Carver?

BK: Of those examples, I’ve only played KR0 – which I would absolutely peg as an inspiration. Beyond its obvious aesthetic beauty, Cardboard Computer demonstrated in KR0 a commitment to purity of vision. It moved games forward another few steps toward being something more diverse and mature. I love and have played games of every type, but I’ve reached a point in my creative life where I don’t want to make things that expose their mechanics and loops in obvious ways. It almost feels profane to me, as silly as that sounds. I’ve worked on enough traditional games, driven by and sold on familiar mechanics — I just don’t want to do that now, I want to be a part of something new.

It’s an exciting time to be doing that, as alternative types of game experience gain more mainstream acceptance. Also, there are just so many indie/alt game creators doing things I find tremendously inspiring. If there’s ever a time where art history documentaries include games, there’ll be people working now that they call pioneers or masters. I certainly wouldn’t put myself in that category, but it’s sure nice to be around when this stuff is happening.