Interview: Resolutiion Dev Team

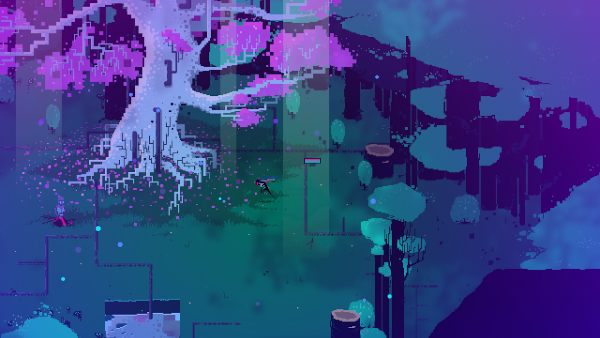

As dirty jokes and the fitful dreams of a god go, Monolith of Minds’ Resolutiion cultivates a unique pixel art feel, treating players to a range of unusual environments, weapons, and NPCs. The brainchild of German devs Richard and Guenther Beyer, the game takes players into the deep unknown, and I leapt at the chance to interview the dev team on its process and game design philosophy.

Erik Meyer: While your game may draw some comparisons visually to Hyper Light Drifter, I see more of an organic, dying monitor feel. You have landscapes of eyeballs and teeth, vines surrounding rope bridges, so while you’re going for an anything-is-possible, dreaming god feel, what guides your pixel art asset creation and the levels that constitute the world?

Monolith of Minds: The best stories always happen between the familiar and the unknown, right?

When we had the mad idea of making a video game five years ago, we were pretty much bored to death by the dominant themes of most games: either high fantasy with orcs fighting elves in the realm of Azewhat, or badass marines shooting up advanced, space traveling aliens, who have no other urge than devouring human flesh. We craved for stories and worlds that felt fresher than a copy of a copy.

While the first prototype was called “Red Wars”, we framed our emerging world as a mix between Star Wars and The Matrix, with plenty of Alice in Wonderland mixed in. Translating this into the realm of video games, we ended up with “Zelda in the future”. The foundation was two short stories I had written years ago, called “The Last Website” and “Story of Red” — both to be re-released around Resolutiion later this year.

From there, the madness took the best of us, as we had no capabilities or skills guiding how to create a thing as complex as a video game. So we picked up everything we liked from various forms of media, throwing together Frank Herbert’s Dune with Sword & Sorcery and mixing Moby Dick with transhumanism and AI theories: permuting all our influences for a while, many didn’t work, but from those that did, eventually Resolutiion was born.

EM: Beyond wild locations, Resolutiion invites players to, ‘Take on a multi-cultural-mashup of cynical gods, emotional machines, zealots, luddites and furry critters.’ When you sit down with a blank page/screen in front of you, what restrictions do you place on yourself, when it comes to adding inhabitants to the game universe? What kinds of criteria inform your decisions and commitment to a particular group of beings?

MOM: Why is an Italian plumber saving the Mushroom Kingdom by kicking turtles in the face? How come Cloud Strife fights characters from Pixar’s Cars on his Final Fantasy adventure?

Video games are amazing tools for telling strange stories that stretch the imagination — particularly because playing is an active process, and the player needs to create new synapses through new combinations: the unstoppable force meets the immovable object.

We got there by basically running two programs at the same time: my brother Richi —who’s an ex-physicist— pushed for a very dark but realistic setting, built on economic constraints, geo-politics and evolving technology. I, on the other hand, was always looking for stupid fun, fantastic elements, and boundless day-dreams. These two dynamics often rejected each other and pushed the envelope of world building, but also kept the other from dominating.

Whenever we created a biome, mechanic or character, we started from a logical point: what’s the backstory? Is this a reasonable feature? Can this be achieved within our world’s parameters? Then we added new elements and ideas that twisted and changed the theme slightly, to make it stand out: can we have petrified corpses in a nuclear desert? Yes — but how about we just scale them up 4000%? So the Desert of Giants was born.

At its core, Resolutiion tells a very simple story about a totalitarian future, based on scientific progress and predictions. But by pushing everything a little out of context, and adding wild bits and hiccups, the whole ride becomes much more enjoyable.

EM: Pixel art, especially as a suggestive medium with a vibrant color palette, takes on an almost Impressionist, painterly quality; regarding the presentation of and interaction with new entities (baddies, bosses, quirky NPCs), how do you see your work best delighting and engaging visually? And as it blends into the audioscape, what kinds of synergy need to happen?

MOM: We grew up as kids of the 80s with the original black and white Gameboy and later the SNES. Therefore, pixelart is what we think of, when we think of games, and at no point did we consider to make anything but a pixelart game. Also big, chunky pixels have this precise mechanical quality, like Tetris or Lego bricks: there’s a clarity and an impact to two pixels connecting what most other art styles lack.

There’s also the presumption that pixel art is simple to learn and quick to execute, which —naive as we were— turned out to be damn wrong: while a few pixels can be drawn or animated rather quickly, they are also less forgiving than other techniques. Each single dot of light counts, and players will recognize errors instantly.

The positive flip-side of this is the high degree of interpretation that can (and often needs to) occur in pixel art: with a face made up of 20 colored squares, there’s little room for details and characteristics, so your brain’s imagination has to make up for it. The result is a highly personalized experience for each player, to make it their own — did you ever wonder how old Link is in the first Zelda game, without having a look at the box art?

Resolutiion’s art style emerged from us learning these things as we build each asset: we hated comic-like outlines and wanted to have plenty of color all over the place, more towards an artistic mess than a technical sketch. From there, I guess we were just stubborn and lucky …

And since you’ve been asking: the audioscapes (sound effects, not the musical score) emerged quite similarly. Richi just dropped some cheap effects from a huge library in there, with the plan to clean it all up as we made some serious progress. But as the game turned more and more into this drug-infused trip through Wonderland, those rough audio-bits started to bring a unique charm of their own to the game: everything sounded a little unusual, kind of quirky but memorable.

All in all, it seems like Resolutiion is just a big pile of chaos, where some serious fun happens in between the cracks — which is pretty much how we build it.

EM: Viewed from afar, Bolshie, Mother, and Badger, Badger, Badger, Badger represent but a few of the goofy but fun examples of oddball in-game run-ins. To my eye, a tradition of zany what-the-hell kinds of characters go back as far as storytelling itself (Frau Perchta, Krampus, Till Eulenspiegel, etc), so as devs, what makes a particular persona interesting and memorable?

MOM: (Note: Badger was just a meme-joke — this guy is simply called “Mushroom King”.)

Well, what certainly does not make an interesting character are the clichés: the noble warrior; the hardboiled spy or the omnipotent sorceress. It’s nothing new that we enjoy the shiny surface, but we really love the small imperfections, the cracks that tell a story. That’s true for things and humans alike.

For Resolutiion, every character or entity started as a primitive blueprint: we have the wise monk, the angry savage, and the shady terrorist. Then, while tying the lore around those guys, we added more fragments to each persona, background stories or extreme features: the Witnesses are just a bunch of random nerds, wired into too much technology. Their boss, the Preserver, on the other hand, is a powerful manager with a clear agenda and the means to implement it. Comparatively, he’s much bigger than the Witnesses, floating above ground, and his speech is much more focused.

The same is true for all the creatures: Bolshie seems like just a goofy, yellow worm, but its story is tied to the death-wish of a little girl called Marty. She then has a dark past with Valor, the main character. In Resolutiion everything is connected and nothing is as it seems. But hey, figuring these things out is why we play games, right?

I guess a key to memorable character design is the balance between what we can quickly pick up and what we need to slowly work out: if everybody is a crazy, over-the-top superhero, nothing stands out. The same is true for a gang of faceless Stormtroopers or 80s street punks. But what happens when that one Stormtropper removes the helmet? Now there’s a face that tells a story.

While technically each person is an individual, our brains only have a certain amount of memory: help me to draw the line between who’s cannon fodder and who’s important — making that one bigger or more colorful is a good start, but these are video games, and we can stretch the boundaries.

EM: On the development environment side, I see you use Godot and Inkscape in your work; you jumped into the game design world a few years ago, so what has the explosion in tools looked like, from your standpoint? Do new options and software make you constantly think, ‘Maybe we should try that,’ or does that quickly become a Pandora’s Box to insane version control issues and mismatched content? In following, at what point has your game development document (as it were) become a relatively stable blueprint, or are you still redefining what you see as possible?

MOM: Haha, of course we are technical guys: we love to tinker with new toys, new software. But for the most part, it just happens around the edges of Resolutiion’s development.

While we are totally new to video games, we have some background in consulting and collaboration: if you want to work with various people all over the world, keeping on top of the technical progress is stressful and conflict-prone. Instead, we learned to work with primitive systems and data-types at the center, while everybody chooses their own tools and processes to contribute respectively.

That means that for the most part Resolutiion is just plain text (Visual Studio Code) and pixels (Gimp), held together by the engine (Godot), and stored on a version controlled server (Gitlab).

For us, developing a game was always about telling an interesting story first, and second about the looks, technical capabilities or possibilities. Even if we would have liked to throw in some 3D or more advanced compositing, it would not have been possible at all for our two-people-team.

EM: As The Onion famously joked, as a nationalistic stereotype, ‘All Germans make good mix tapes.’ And I could posit the same about the development community there. From Death Trash to Saftladen Indie Games Collective, Daedalic Entertainment, Osmotic Studios, and others, there’s a lot going on in Deutschland. How do you see your local/national connections influencing your work, and what cultural madness comes from the world you’ve come of age in?

MOM: Man, I really love your questions. That’s another great one, that really gets my gears grinding. Though, the unfortunate answer to the question of Germany’s influences on our game-work is: absolutely nothing.

I’m aware that Germany has nothing compared to a “Skandinavian design sensibility” or a Japanese calligraphy heritage that subtly influences all artistic endeavors. After two massive wars in the last century, most of what could be seen as German culture has been whipped out and replaced with international ethics & aesthetics. We grew up, barely thinking of our country being more than some lines on a map and a shared language.

What I do perceive. having traveled the world a bit, is a typical German feeling of hysteria: people are slightly more afraid of the future and therefore plan longer and often work harder, consistently — we make great worker bees. Also we have a crazy amount of regulations and taxes, particularly impacting smaller companies. Therefore, if a German wants to get a business going, it’s serious, haha.

So yeah, maybe this stubborn, persistent mentality is a German characteristic that we definitely have, and maybe many other game developers share as well: just grind on until it ships or you sink.

EM: Given your many-year development of Resolutiion, beyond your honing of basic dev skills (art integration, coding, etc), how has the process of honing your project over a longer period of time shaped things overall? Have you found yourselves ripping out and revamping chunks of code/art assets frequently along the way, or is it more of a gradual, iterative process akin to the mammalian brain built atop the reptilian brain (and so on, and so forth)?

MOM: Certainly the earliest mindset we had to adopt was “learning to learn”: with no experience, we obviously had to pick up new skills by the month. As soon as we became a bit more fluid in one area, the next few challenges were already waiting.

At the same time, while we learned, the whole game world and scope grew and grew around us: the four original areas turned to seven and then to 10 areas, all doubling its size and complexity. While the space itself became bigger, we needed to populate it and tie everything together: Valor and Alibii are on a journey of growth; they meet others and the human drama unfolds; new regions emerge, backstories are uncovered, politics and economics influence everything.

Keeping such a complex system moving forward while staying on top turned out to be the real challenge for the two of us. Again, we developed two dynamics that balanced each other and us personally: on one hand, we constantly implemented and tested items, enemies and mechanics; reworked them, changed them or discarded them. On the other, we just fooled along, building new spaces, introducing new characters, excited to see what’s behind the next corner.

So shifting between boring but valuable iteration and an ongoing sense of curiosity about Resolutiion’s world kept us motivated for those five years of learning. In fact, we still have enough unanswered questions for the next three games, haha.

EM: You’ve done a press demo and shown a lot of content via social media, but as you look ahead to the game being in the hands of players around the globe, how do you see your development cycle changing, post-release? Can players expect radical shifts in the game via content updates (expanded areas, new bosses, etc), or will you focus more on blowing our minds up front and making sure everything is optimized/debugged/pristine as gamers crawl across every pixel and in-game tile?

MOM: At the moment, we are tied up in the basement of our publisher Deck13, and I don’t expect this to change throughout 2020. It appears to be a theme in this interview, but there are again two sides of the coin: we as creators have put almost everything into Resolutiion that we envisioned. But there are a few more things we want to see turn from idea to playable experience. These will follow in the shape of a few content updates or DLCs after the game’s launch in the summer.

Then there is the other side of reception and sales that pay the bills and let us stick to the project for a little longer. This side includes plenty of promotion and marketing, interviews like this one (unfortunately most are less interesting), interaction with players, feedback, bug fixing, and just making sure that what’s there works and sells as well as possible.

That being said, we love our indie games rough and edgy: players should be able to exploit bugs, experience glitches, and ultimately speedrun Resolutiion by harnessing every kind mistake on our side — let the Ghost in the Machine come forth.

We’ve already set ourselves up for supporting Resolutiion for at least a year or longer. But that will certainly not keep us from coming up with new ideas to expand our lore and explore it: we never set out to tell a single story, but rather to build a fantastic world that houses many tales — Resolutiion is just the introduction.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=qN3q0MVXNTM&feature=emb_logo