Interview: K’NOSSOS’ Nikola Vetnić

Using a 2D abstract expressionist style, Svarun Entertainment has been building K’NOSSOS for some time, honing the adventure into the cosmos while maintaining a sci-fi edge that reels in players. I chatted with developer Nikola Vetnić on his project’s quirks and triumphs, noting the game’s novel feel and exploratory freedom.

Erik Meyer: The game’s art style represents a throwback to yesteryear yet meshes well with sci-fi elements. As a dev, how did you arrive at this particular look, and what challenges have come with it?

Nikola Vetnić: To be completely honest, the path we took with the art direction of K’NOSSOS was one taken more out of necessity than it was the one we preferred from the onset. The initial art we produced was a lot more in line with the conventional, gritty, dark sci-fi setting the audience was already familiar with from the popular cinematic releases and games; however, the team I gathered initially broke up rather quickly (not at all surprising given we all were – and still are – working pro bono) and at that point, it became obvious that I could never keep up with all the dev duties and at the same time produce the photo-realistic sci-fi pieces we started out with on my own.

So, the art direction of the future game was a burning question. I was thinking. Thinking a lot. I was also keeping my eyes open. During my consultation hours (I work as a professor of music at the teachers’ training college) I had a lot of time to do both, and it just so happens that I took a closer look at the painting hanging on the cabinet wall:

(Wassily Kandinsky – Picture XVI. The Great Gate of Kiev, 1928)

My personal understanding of such abstract art is that it could be viewed as a fresh and somewhat alien representation of objects and themes we are used to seeing in our everyday lives. In its primitive and basic qualities, there was an aura of mystery, there was something intriguing and unexplainable, something constantly pushing the spectator to ask “why?” over and over again – just the kind of atmosphere I wanted for my dark sci-fi story. It was also a style standing opposite to the currently dominating trend of realism in computer games – it is rather funny that a medium as capable of delivering such diverse content as this one moves more or less on several predetermined stylistic “paths” and rarely strives for something truly different (probably due to fear of commercial failure). Last but not least – from the technical standpoint – this was a style not impossible to follow with my modest technical skills; there was even a chance of imbuing this visual language with words and phrases of my own.

The first few pieces created utilizing this approach are currently residing in Chapter III of the game. You have asked about the challenges – at first there were none. Really. I remember the first piece took me mere days to complete in 3D, plus a week or two for the Photoshop paint-over by the 2D artist. It was amazing – monumental, cold, alien, foreboding, but also appealing and attractive in an enigmatic way. After those initially successful pieces, it became apparent that one can only do so much with the basic geometrical bodies and forms. In reaction, I’ve broadened the “palette” of “acceptable” building blocks I would use in future scenes. This in particular was, and still is, the biggest challenge of K’NOSSOS – staying in line with those original self-imposed artistic restrictions, while at the same time keeping each new piece produced as fresh and as interesting as was the case with the first one. So far, we are managing to stay on top of things, but it gets trickier, as the amount of visual assets is constantly growing.

EM: What do you see as key to a classic adventure game drawing an audience? What elements are essential, and what laid the groundwork for the project?

NV: I believe that success of any adventure game – classic and modern alike – lies in the fragile balance between the story design on one end and puzzle design on the other, as well as the presentation through which these two elements are communicated to the player. An adventure game needs a great story because it serves as the prime catalyst to get the players’ excitement-inducing mental juices going, similar to great action gameplay in shooters or excellent level design in platformers. However, an adventure game is not a piece of literature – this great storyline cannot be laid out in the open for the reader to consume as quickly as he or she can read it. This is where great puzzle design kicks in – poorly designed adventure gameplay feels like a crude blocking device put up with the sole purpose of preventing you from finishing your picture book once you went at it; great adventure gameplay design incorporates the puzzles into the story itself, and the person playing the game never has the impression of barriers artificially set up to meddle with the fun. Finally, this balancing act needs an elegant and functional representation, hopefully deprived of all the fancy gizmos and gadgets advertised as groundbreaking mechanics, but that are, in essence, not all that functional or even needed, or are simply old-school stuff dressed in a shiny attire.

That said, I believe the classic adventure games have done this job the best. From the mechanics point of view, the adventure genre has that misfortune that it appears (at least in my own opinion) rather stiff on the surface, perhaps too strictly defined, and a bit rigid. A lot of contemporary adventure games have tried to mix things up and introduce new mechanics into the cauldron, perhaps attempting to create cross-genre hybrids or even trying to reinvent things from the ground up. The latest trend I have managed to single out is the introduction of casual elements into adventure gameplay, leading sometimes to absurd titles devoid of gameplay altogether, which put all the emphasis on the story and a passive unfolding of the said element. The degree of success varies from case to case, but my humble opinion is that the results are not all that magnificent.

Before the development of K’NOSSOS started in earnest, I asked myself: do we really have to fix the classical formula which is obviously not broken? Of course not – hence the decision to present K’NOSSOS in a way familiar from the best-known classics of the genre. To quote our promo material:

K’NOSSOS plays like most of the classic titles in the genre. PC, viewed from 3rd person, traverses the locations presented in side-view. Using a classic third person interface, the player is able to interact with the world through a player character (PC) avatar. Left mouse click is used for moving and interactions, and the Right mouse click is used for examining objects further.

In addition to this, we have put huge effort into crafting a unique and captivating story for our game, as well as enriching it with sensible and well-integrated puzzles and problems which should at no time feel forced or artificial. Combining this with the weird and intriguing visuals, we were confident that we have laid the groundwork for something worth showing to the world.

EM: Indie games have a number of engines to choose from, so what went into the decision to use WME? Why not Unity or Unreal?

NV: Unless a programmer is at the helm of an indie team and therefore basically developing his/her own game, it’s a very tough job finding someone to code for you, unless you have secured substantial funds for the project. I have spent a lot of time trying to figure out that part of the deal by involving various people with diverse backgrounds but, sadly, none had what it takes, be it for lack of expertise with games or programming in general, no time to commit themselves to the project, or simply wanting to make quick buck and realizing it’s not going to happen that easily.

It was August 2015; I remember getting up from an afternoon nap when I got the message from Jonathan (who is now probably the most important person on the K’NOSSOS project) offering a hand with the game. It was natural that I was skeptical at first – people write all the time offering help in different areas of the game dev process. However, it turned out Jonathan was a real deal – he has serious background in “serious” IT industry, he has led tons of important projects for major employers all over the world and had recently decided to pursue his dream of developing adventure games (I was lucky he didn’t pin his resume to that first email as I would’ve written him off as a troll). More so, he has already worked on several uncompleted projects, all developed in (the now already quite outdated) Wintermute WME engine by Jan “Mnemonic” Nedoma.

I was thrilled to have such an expert as a permanent addition to my team, and if he had said that he would prefer to code the game in Modula-2, I would probably have not objected. However, we had several good reasons for sticking with WME. First of all, Jonathan has used WME for a number of years, and it was an environment he was quite comfortable in, unlike those of Unity or Unreal. Second, WME was created specifically with adventure games in mind, unlike Unity or Unreal engines which, although they surely can be modified to serve such a purpose, are best suited for games in need of a 3D environment. Finally, we were confident that WME could deliver a game such as K’NOSSOS and also do that with minimum amount of experimentation and learning (though at cost of some limitations that modern engines easily lift), which would in turn reflect itself on making the dev period shortest possible.

In the meantime, we are exploring the possibilities of Unity and are planning to make a switch with the next project we embark on. The biggest plus in its favor is multi-platform support, the lack of which is the biggest hindrance when it comes to WME and the primary reason as to why K’NOSSOS is, at the moment, limited to being a Windows-only product.

EM: I’m interested in the color choices you’re using for the in-game assets. As opposed to a neon or vibrant color palette, the game has a darker feel. Can you describe the connection between the visual elements and the game universe?

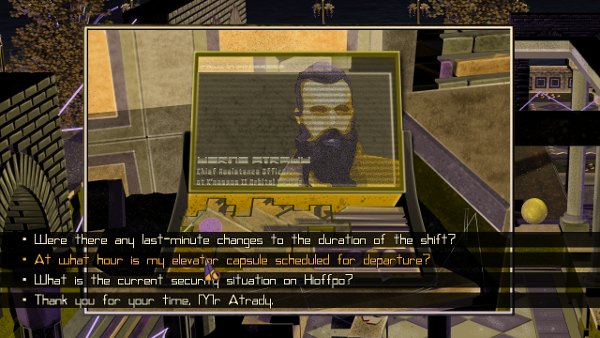

NV: I have mentioned self-imposed artistic restrictions earlier in the text; those are quite common in composition practice and are (at least in my case) often quite arbitrary – you present yourself with conditions and thus the “environment” and then you start wiggling onwards and see where it takes you. One of the initial drafts of the K’NOSSOS script revolved around radically different circumstances that the PC found himself in as the chapters of the story progressed; I have decided to represent these with starkly contrasting color schemes between subsequent sections of the game. The initial draft of the story has changed quite a bit since then, but this artistic idea stuck and what you can see today is the result – we have the gold-purple-black scheme for the interface and the Tutorial section, and we have the yellow-green-magenta in the Prologue. Explaining the connection of the color palettes with the script fully would ruin much of the game for the players. Suffice it to say that each new chapter peels away a layer of skin obstructing the vision of the PC and obscuring his sight, bringing him closer to learning the truth of what really happened to him and the places he visits; such enlightenment carries with it a drastically different view of the surrounding world symbolized by the shifting color of that which the PC observes.

I have allowed myself plenty of liberty when it comes to the choice of particular colors that make up a scheme. For example, the “interface” palette of gold-purple-black is a reminiscence of the palace levels of my first “serious” video game – the Brøderbund’s Prince of Persia from 1989; the Prologue section’s color set is a reminiscence of me seeing an Amstrad Schneider CPC 464 with its sickly green monochrome display in action as a kid; the red-gold-white scheme of Chapter I is supposed to symbolize the nostalgic sentiment of autumn – you’ll figure out why once the game is out and the full story is revealed. It is interesting that, despite not being inherently “dark” in an emotional sense, these palettes impose such an impression on a spectator; for this I “blame” the architecture of the sites and the lighting thereof the most. This, by the way, is done on purpose; while some may not agree, I find the art of Kandinsky quite dark in its indifference in regards to human understanding and emotion. Such indifference is also present in the art of K’NOSSOS, perhaps even amplified by the colors we usually see as pleasant and cheerful. Setting up such contrasts is something I have found to work quite well in what I am trying to achieve.

Also, these unusual and arbitrary choices are, as I see it, amongst those that ensure the enduring freshness of the visuals in K’NOSSOS, while also keeping things consistent and preventing them from going over the top. There are a lot of theories regarding the colors and the mixing thereof, but I do not consider myself a visual artist and am thus not unconsciously bound to obey those rules. More so, these theories are part of the canon and by playing according to such guidelines, one is guaranteed to obtain a classical result. As an experimental indie developer, I am trying not to (re-)achieve classical but to find new solutions for the problem of visual representation in games. Even if I could afford it, I would not want AAA quality art painted by the hottest artists of the industry, simply because I find such pieces quite boring. From time to time, I read about painstakingly recreated architecture of this historical site or that interesting building in such and such a game; that is all fine and well, but what about the fantasy, what about the possibility of exploring that which does not exist in real life at all? With K’NOSSOS I have uncovered a painfully obvious fact – we, the artists and game developers, have all the possible freedom in the world. We should put it to good use as often as we can.

EM: You’ve put the game’s alpha demo out there for people to play, so what kinds of responses have you been getting? What kinds of feedback have been helpful?

NV: The most noticeable elements of K’NOSSOS are unsurprisingly the visuals; the majority of comments we receive are tied to the unusual graphical presentation of the game and so far those are, I am proud to say, overwhelmingly positive. Another topic which mostly reviewers and journalists find interesting is the “Minoan connection”; what is the link between K’NOSSOS and Knossos, is PC some kind of high-tech spacefaring futuristic Theseus, is there going to be a minotaur involved, what exactly is this story about – these are some of the questions I found raised in numerous articles across the web. Finally, there is also positive feedback in regards to the audio of the game – it seems that experimental music is not that scary once put into a broader context (which is a revelation for me, to be honest).

Of course, not everything went nice and smooth – we had a few bug reports as well, though most of those happened during closed testing prior to releasing the demo and we’ve managed to patch those up before release. While not a response strictly speaking, we’ve gotten in touch with several very nice and helpful people online following the demo release who were happy to lend us a hand with online promotion and marketing, an area in which we were desperately needing assistance.

EM: Games have to balance beautiful assets, engaging play, and compelling storylines, so how do you see the project advancing in each of these areas? Where have you been putting your time, recently?

NV: The backbone of the project – the script – has been completed and double-checked a long time ago and for me, and that crosses out the main concern from the list when it comes to the dev process of K’NOSSOS. The game world has been completed in 3D, and we are now mostly rendering various camera shots and choosing the best ones for the latter 2D overpaint, and as far as 2D is concerned, we have our 2D artist on stand-by whenever we need her. What lies ahead is the application of fine polish to gameplay of the next major chunk of the game, which will include Chapters I through III, as well as figuring out the details of scripted events, puzzles, and dialogues and building them in the engine itself.

However, recently I have been putting most of my time into promotion and marketing, as well as doing the internet legwork as much as I can, because, as my previous project VSEVOLOD has taught me well, even if the game has redeeming qualities, it won’t do you any good unless people hear about it. I do not consider myself a social type, so all this socializing (and that’s what it is basically) is giving me a hard time, but there’s no way around it unfortunately. You gotta do what you got to do.

EM: Each sci-fi game universe has its own flavor, so what do you see as key defining elements of the world you’ve created? What kinds of history, technology, etc, drive the events we’re thrown into?

NV: Ah, well… That one’s a tricky question. It’s tricky because it’s hard to answer any of those without spoiling the story, and the story hasn’t even started in earnest in the Prologue section which we have revealed to the players with the Alpha Demo. I’ll try to drop a few hints without messing with the experience we’re hoping to deliver too much.

Key defining element of the universe of K’NOSSOS is probably scarcity. It is not a debilitating scarcity – there is enough food and water, energy is also pretty easy to obtain – yet there is an ever-present lack of materials crucial for civilization to progress beyond a certain point. So, the crucial resources are rather scarce and, as it is evident from the Tutorial section where players learn that the PC is gearing up to leave for planet orbit, those resources that ARE available are being mined off-world. The Tutorial also hints at a conflict involving at least two groups suspended by an uneasy truce, a conflict fought over control over access to this orbital mining complex. Yet, despite this, the Tutorial shows the PC in his serene urban home and also mentions his family leading a laid back existence with no threat looming on the horizon. In conclusion, this scarcity produces certain hardships, but these hardships are nowhere near catastrophic.

Another defining element of our story is discontinuity. The Tutorial paints the PC as a family man with a somewhat unusual job gearing up for what seems to be another boring day at the office; the Prologue tells the story of a lone engineer manning the massive colonization vessel in the far-flung corner of the galaxy being brought back from cryo-sleep only to perform a few insignificant maintenance tasks so that he could get on with his duty. Whether this is a same person or not, whether there is a connection between these men or not is a tough question at this point.

The PC also mentions a material called “Alloy” in the Prologue. Seemingly unrelated items – a transparent metal panel, a piece of chain – are, according to the PC, made out of the same stuff. I would single out this material as being the third defining element of the story. I always mention Dune as one of my main sources of inspiration no matter what I do – Alloy could perhaps be understood as a wonder-material similar to spice. This would coexist well with the scarcity I talked about earlier, as it is the similar situation to what we have in the Duniverse. However, things are not all that simple; Alloy is so much more, just as the Spice turned out to be so much more than the wonder drug which expands life and grants prescience.

I can recommend reading all the comments and dialogue lines in the game carefully. I have went over anything that appears in the game at least two dozen times and I assure you – not a single word is left in the final version unless it contributes something to the story. Regardless of whether you “decode” and connect the dots correctly or not, there is an interesting experience to be had from observing the clues and attempting to piece together your own story.

I almost forgot to mention – Dune also has worms.

EM: Tell me about the Svarun team and your process together; how do you coordinate your differing roles, and what does a typical day look like?

Core team consists of Jonathan Hopkins – a great guy from the British Midlands who mostly does coding but also is of tremendous help with the internet and marketing side of the deal, Biljana Jelicic – a skilled 2D artist from Novi Sad who was kind, brave, and hard-working enough to stick with us for all this time, and myself. Occasionally, we hire additional people to do stuff we ourselves cannot, and also there has been a number of friends and colleagues who helped with bits and pieces over the development cycle.

Coordination is the easy part because it’s mostly Jonathan and me cooperating on daily basis, given that there is comparatively less work for Biljana once the 2D art is prepared and put into WME. The foundation of the project is of course the game design document where I try to meticulously describe the game events in a coder-friendly way so that Jonathan has to do as little decoding as possible. Once that is ready, I ship it over to Jonathan with all the accompanying graphics and other assets, and then he goes at it. Once the materials are incorporated into the project, he does a build and sends it over for a check-up. Anything that is not the way it should be, both of us input into our spreadsheet as either bug, enhancement, or comment, often accompanied by screenshots and/or playthrough videos. Once the check-up is done, Jonathan takes the list and clears issues, one after the other. While we both have day jobs, we are also extremely lucky that we are both teaching, hence we have loads of time to throw at the K’NOSSOS project; we do not have set work hours – we simply work on the game whenever there’s time to spare and whenever our families don’t present us with ultimatums for dodging home duties too much.

In case you missed it, here’s the trailer: